To dive or not to dive?

One of the basic rules defining safe diving is that one should not dive “by force”. If the conditions at the dive site and the level of difficulty of scuba diving exceed one’s skills and equipment capabilities, according to good diving practice, one should then forgo entering the water and stay on shore. In reality, unfortunately, it looks a little different. There are many cases that divers decide to perform a given dive despite poor weather or terrain conditions, the lack of support from the shore, incomplete or inoperative equipment and the fact that the dive is, for their skills, far too deep or too long. It should certainly be said that such behavior is wrong. But can it also be said that it is incomprehensible? Is it possible in certain cases to allow oneself to take risks, or to uncompromisingly adhere to the existing safety rules and principles? Well, the answer to this question will not be easy, and certainly not unequivocal, especially with such a controversial topic. However, let’s try to take a closer look at the issue and consider the topic from two opposing points of view.

Safety above all

One radically extreme concept is that a diver cannot afford the existence of even the slightest risk of danger while diving. This risk should be so small as to be practically zero. This looks very beautiful in theory, but in practice it is impossible to realize. By definition, the very act of going underwater, i.e. to a place that is not a person’s natural habitat, increases the risk of loss of life, which contradicts the fundamental basis of the concept of total safety. However, it is possible to get out of this trap by creating a risk prediction model. Any model must, of course, have an ideal state, or situation. In this situation, the diver:

- Is in perfectly clear water (with transparency equal to that of the air), without ripples or any objects floating on the surface

- Is at a depth that allows him to reach surface on exhale on his own

- Is equipped with 100% operational, unused and completed equipment

- Has a full supply of breathing agent

- Is fully rested, healthy and is in very good mental and physical condition

- Is perfectly familiar with the shape of the bottom, the landmarks, the vegetation found there, and the location, dimensions and shape of all objects under the water

On the shore, on the other hand:

- There are ideal meteorological conditions (daytime, no wind and cloud cover, standard conditions [25 oC, 1013 hPa])

- There is a diving base or belay equipped with efficient and complete rescue equipment

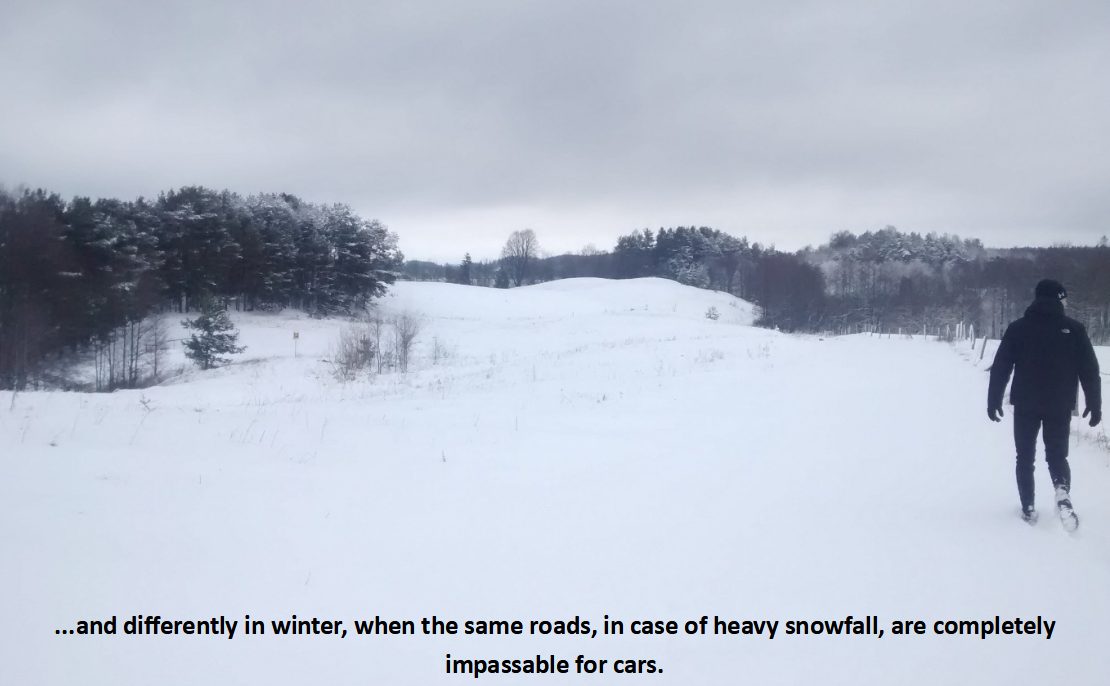

- Access roads to the dive site are well marked, paved and adequately wide

A situation like the one described above should be taken as a baseline, i.e. one in which the value of risk is zero. Any change in the parameters of the model therefore also carries a change in risk. For example, as time under water increases, the value of risk increases due to the decreasing supply of breathing agent. The magnitude of the risk can also be kept constant, for example, by decreasing the depth of the dive as the breathing medium depletes, which is just a simple ascent. Of course, both examples are very superficial, dealing with only two of the above-mentioned parameters, and their sole purpose is to show the assumption on which the above model works.

Adopting such a solution allows you to create a certain reference point for yourself and help you decide whether or not to enter the water in a given situation. The undoubted advantages of the risk forecasting model are its flexibility and the ability to specify precise output parameters. This flexibility involves introducing, if necessary, any additional number of assumptions (e.g., the diver’s level of training) albeit those described above should be the necessary minimum. On the other hand, it is possible to accurately determine the output parameters, since most of them are measurable and defined by numbers, such as the wave run-up (in degrees of Beaufort) or cylinder output pressure (in bars or psi), and some can be determined experimentally, such as the depth from which a diver can emerge apnea. So, going back to the main idea of the safety concept, using the risk prediction model it is possible to distinguish situations in which the planned dive will be safe and acceptable, and those in which one should absolutely not enter the water.

Graduation of difficulty

A completely different concept, on the other hand, is the claim that the development of diving skills can only be achieved by diving in increasingly difficult conditions, posing new challenges all the time. The validity of this approach may be supported by the fact that it is in fact the basic foundation of most scuba courses, in which the student gains experience by diving successively to greater depths. Also, the exploration of unknown or virgin bodies of water, quarries, caves or other underwater sites carries a much greater risk of danger than when diving in an already explored body of water. However, it is such dives that allow you to discover new places to practice the sport and increase your knowledge of the underwater world. Every dive site, even the well-traveled ones such as Molnár János in Budapest, Arch in Egypt or our native Koparki, has those first, virgin, dives into the unknown. Thus, in this approach, the emphasis is definitely on going underwater despite any difficulties or obstacles that arise. This can even be called “diving at all costs”, where each emerging problem, unforeseen event or difficult diving conditions are a kind of challenge for the diver, a test of his skills, as well as an opportunity to develop them. Examples do not have to look far. It is enough for each diver to reach into his memory, and he will certainly recall a situation that he heard about or witnessed himself, and which perfectly matches the ones described above. It should be borne in mind, however, that such actions are justified only if their participants draw appropriate conclusions from them and implement them in the future. Otherwise, such actions do not make the slightest sense, and only lead to unnecessary risking of one’s own life and, even worse, the lives of one’s diving partners.

The influence of random factors

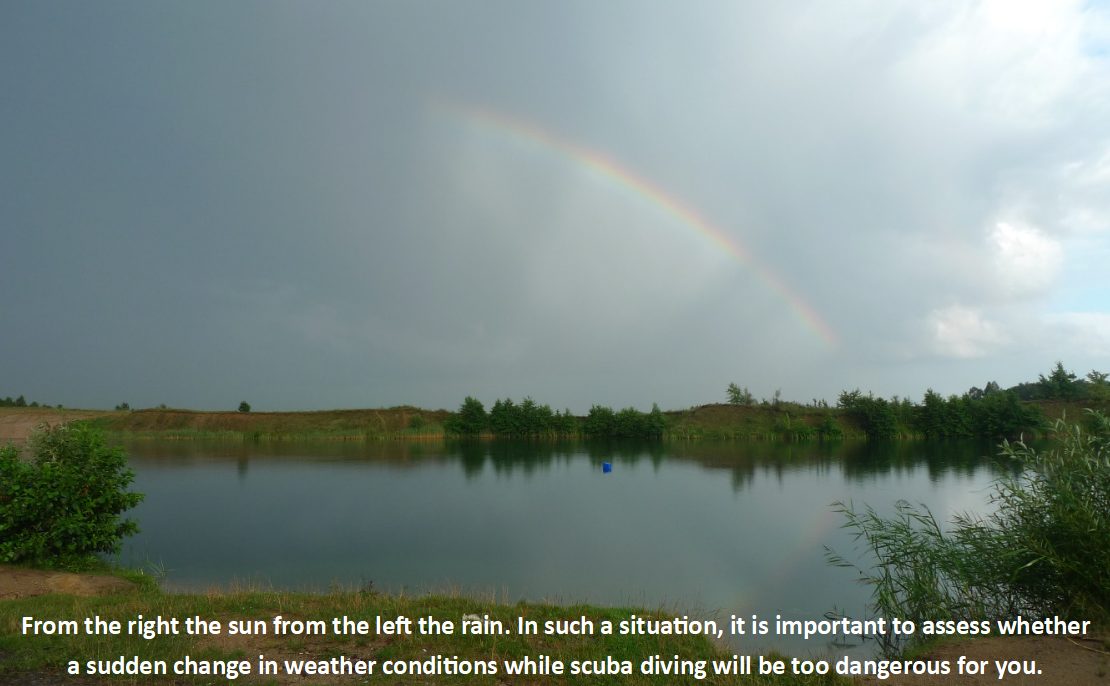

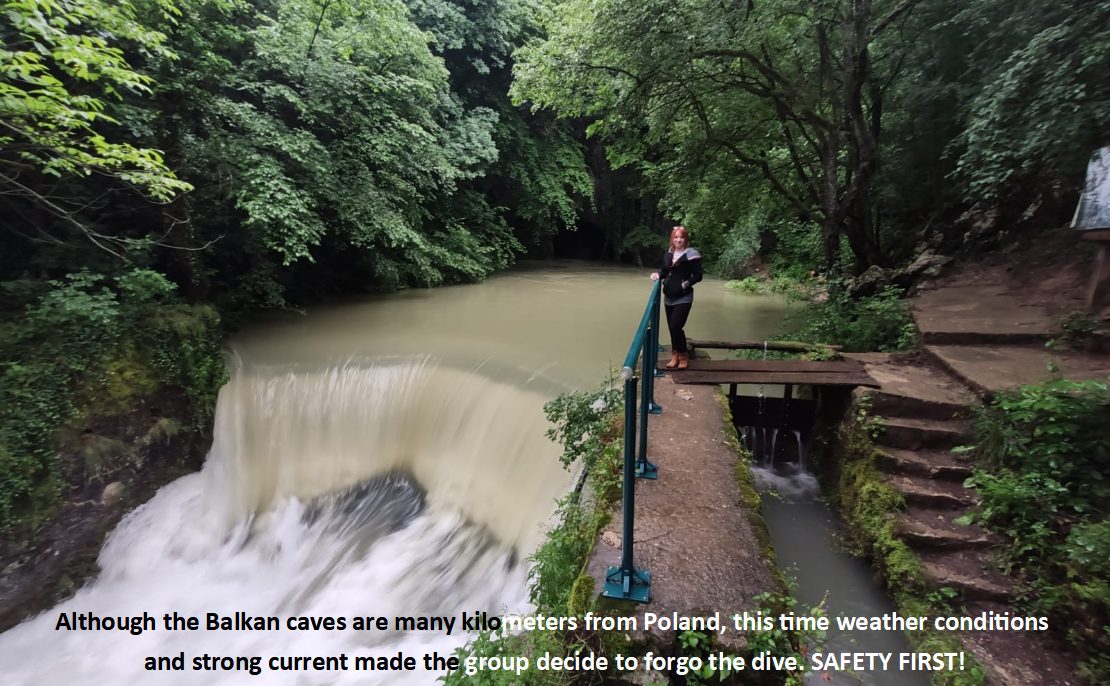

One should not forget about another important issue affecting the degree of risk in scuba diving, namely the random factor. Unforeseen events accompany man throughout his life, so it is logical that they also occur in scuba diving. But what if such a situation seriously hinders or even prevents the execution of a planned dive? There may be many examples: an undercrewed cylinder, from which part of the respiratory fluid has escaped, a sudden indisposition of the partner, problems with balancing the pressure after going underwater or an unexpected change in the weather are just some of the problems that can make a dive dangerous, if we decide to go underwater after all. Many times, despite the obvious danger, the desire to perform a dive, reinforced additionally by the long way to the dive site, the costs incurred or simply a unique opportunity to dive in a particular body of water turns out to be stronger. Unfortunately, the aching heart of a diver is not a good advisor by which it often suggests a path that may be comfortable and interesting, but is certainly not safe.

So what should one do when faced with such a dilemma? To dive or not to dive, that is the question…. Which concept to choose? Safety beyond all reason or diving despite the obvious risks? And what if it is not us, but malicious fate that makes a particular scuba dive too difficult or dangerous for us?

Certainly, one should not choose only one of the extreme options described above and unconditionally stick to it. Such a course of action leads to unnecessary risk to one’s own life and the lives of others, or to limiting oneself too much in diving trips, and consequently to frustration, discouragement of scuba diving and fear of the water. The ideal solution here, is to create a golden mean for yourself, in which you challenge yourself and make difficult dives, but without putting yourself in unnecessary danger.

The role of a mentor and dive partner

If you are diving in a larger group of friends or acquaintances, it is worthwhile for the group to have a mentor. The person who has the most diving experience, plus is liked and respected by others. It is also important that such a person has a calm and strong character and thinks in a mature way. Such a person, in moments of indecision, would be able to influence the group and make decisions to perform a dive or cancel it when opinions are divided. A strong character will also allow him or her to stand up to other divers if he or she feels that it is dangerous or too difficult for some members to perform a dive under the given conditions, despite the fact that some in the group think otherwise. Of course, all sorts of decisions are best made through discussion, but it is the mentor’s opinion that should be decisive or influence the opinion of others. An experienced leader can appropriately maneuver between the concepts of safety and risk and decide which to lean toward more under the circumstances.

Depending on the situation at hand and the point of view taken, he can decide whether or not the whole group goes into the water, or if the dive is too difficult for only some of the people, he can divide it into several smaller teams that will perform dives appropriate to their level of experience and skill. Having a good mentor in a group of divers gives very great benefits to all members of the group and significantly increases the safety of the entire group both underwater and on land.

There is also a certain analogy to group diving in pairs, with the difference that there is no mentor or leader figure, but only two equal persons. In such a situation, the most important thing is mutual understanding and the right dive partner. Diving often with the same person makes it possible to get to know each other, their character and skills better. It creates a kind of bond that is not tinged with any negative emotions like fear of disapproval or the desire to impress the other person. Consequently, this allows for proper judgment of the situation above and below the water and joint development of ideas about whether to dive or not. Mutual decision-making and mutual understanding, important especially in cases where the diving partner or his sudden indisposition is the reason for not going underwater, allows you to significantly increase the safety of both divers and gain experience faster, knowing, even during difficult dives, that you are swimming with a mature and poised person who will not hesitate to provide assistance in a difficult situation. If, on the other hand, you frequently change diving partners, it is worthwhile, in the case of contentious situations, to apply greater safety conservatism and not to make a dive on which we would normally decide to go with an experienced and familiar partner. At all times it should be remembered that it is on us and no one else that the responsibility for our own life and that of our partner lies, and this fact should absolutely be put first when deciding to go underwater. It is worth developing self-restraint and the ability to think logically and soberly assess the situation, because sooner or later everyone faces the dilemma of whether to dive or not to dive, and the price for making a bad decision can be very high, and by no means is it about bad memories of the trip.

About the author:

Daniel Poplawski is an experienced IDF Master Diver Instructor originally from Masuria in Poland. He is the author of many training presentations used by IDF instructors. A chemist by training, Daniel applies his knowledge to the more rigorous aspects of diving, such as gas blending. Privately a fan of healthy living and activity with his responsible and enthusiastic attitude he infects new diving students.